During these times of quarantine I’ve become very familiar with my neighborhood sidewalks, using them as new hiking trails. These neighborhood hikes have afforded me a new way to observe a city street landscape, and as a plant pathologist I’ve used this time not only as exercise but to also track common plant disease issues by just keeping my eyes open. You’d be surprised to know how many sick plants are out there to see!

While azaleas, rhododendrons, and Japanese maples are in most neighbors’ yards (and they sure are pretty right now!), I see pachysandra patches nearly everywhere. It is certainly a beloved plant, and very successful as a groundcover. Pachysandra prefers part to full shade and is typically quite low maintenance. The plant naturally grows into a dense carpet, and while this growth pattern usually doesn’t provide any reason for concern, if environmental conditions are right and a particular pathogen is present, disease in a pachysandra patch can spread fairly readily. And that’s exactly what I’ve been seeing this spring.

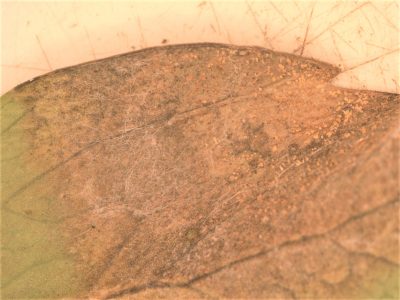

Volutella blight, caused by the fungus Volutella pachysandricola, is a common destructive disease to pachysandra. The disease presents as brown lesions on the leaves, often with a concentric circle pattern. The lesions expand in size until the whole leaf turns brown-black and dies. Lesions also occur on the stems, causing plants to wither and die back. Orange-pink masses of spores can be seen within lesions during wet and humid conditions. Plants die in patches, and disease spread usually appears in a circular pattern in a bed.

The classic dense planting culture of pachysandra increases the humidity in the bed, providing ideal conditions for Volutella blight to develop and spread. Further, because the pathogen thrives in cool, wet weather, all the rain we’ve had this spring in the Northeast has contributed to disease development as well. Because pachysandra plantings are usually so low maintenance, they can be easy to forget about. As such, stressed plants are more susceptible to Volutella blight. Stress from drought, winter injury, pruning injury, or insect infestations can also contribute to the spread of the disease.

To manage Volutella blight, only work in plants when they are dry, because the fungus moves through water splash. Remove infected plants and destroy them; do not compost as home composting systems typically do not reach high enough temperatures to kill spores. Thin the planting to increase airflow, which also will encourage plants to dry out more quickly. When thinning, sanitize tools with a 10% bleach or 70% rubbing alcohol solution to not accidentally infect new plants. There are fungicide options to help manage Volutella blight, but will only be useful if these other measures are taken. They will not cure infected plants.

So, head outside today and check on your pachysandra patch. Might be time to give it a little love!

However, new strains of PVY have evolved to make it more difficult to notice an infection until it is too late to do anything about it. Viruses are capable of evolving to change the symptoms they induce in hosts in order to continue to thrive.

However, new strains of PVY have evolved to make it more difficult to notice an infection until it is too late to do anything about it. Viruses are capable of evolving to change the symptoms they induce in hosts in order to continue to thrive. The other way PVY is spread is through infected seed. When infected seed potatoes are planted, they result in infected plants. These infected plants then are a source of PVY inoculum for aphids.

The other way PVY is spread is through infected seed. When infected seed potatoes are planted, they result in infected plants. These infected plants then are a source of PVY inoculum for aphids.